By Nan Frydland, MEd TESOL, Literacy/ESL Instructor, Mercy Learning Center, Director of Corporate Social Responsibility, Frydland & Co., LLC

Listen to Nan talk about her work in this webinar clip, Using WhatsApp for Remote Instruction.

As a practitioner of culturally responsive teaching who works with adult Students with Limited or Interrupted Formal Education (SLIFE), I resisted integrating technology in ESOL classrooms for a long time. Learners from cultures so different from our own are often unaccustomed to formal education, so just “learning school” is a challenge. It’s my job to reduce their cultural dissonance and to accommodate and adapt to their preferences for orality, collaboration, and personal connection in the classroom (DeCapua, Marshall, & Tang, 2020). We do that in my basic and level-1 classes by creating charts of data on huge pieces of paper on the wall, exchanging personal stories, drawing maps, engaging in activities outside the classroom, and putting all of it into looseleaf binders that serve as our custom textbooks. We critically challenge our commercial textbooks, discuss current events, and occasionally make posters and go to the streets in demonstrations. The purposes of education as I see it are to attain literacy for meaningful purposes and to be prepared to fully participate in society as critical thinkers (think Freire).

Digital literacy in this framework simply posed an additional layer of difficulty for students to overcome, and prior to mastering enough English to understand directions to use digital devices and platforms, I believed students’ time would be better spent acquiring the real-life skills to navigate the world and make one’s place in it. In fact, prior to the pandemic, my students described all kinds of needs, including having the verbal skills to conduct ordinary tasks like shopping and banking, getting jobs in restaurants, construction or home care, and talking to family members proficient in English. No one wanted to learn how to use the internet and few learners had email addresses, computers or home Wi-Fi. Most have smartphones for calling family and friends, exchanging photos, or translating in school, and when asked to use the phone to engage in online textbook exercises, they were reticent. The screen was small, the instructions confusing. Just last semester, it was a challenging task for students to download and use QR codes for textbook exercises. In one class, we had a Smartboard, and used it to watch We Speak NYC videos, collaborate in creating maps and charts, and practice listening exercises from textbooks. Then COVID-19 came to town.

Pandemic Pivots

In large, multi-class emergency meetings, school leaders provided instruction in English, Spanish, French and Haitian Creole for downloading WhatsApp, a free messaging app. Back in our classrooms, we formed WhatsApp groups so that teachers could contact an entire class with one text. Individual teachers scrambled to access Zoom and Google Classroom as the governor shut down all the public places where students might have accessed WiFi. It was Friday the 13th, and I was dumbfounded. Without a plan, I texted my two classes and instructed them to meet on WhatsApp the following Monday at our usual class times.

To suddenly be deprived of our usual means of communication, both from their cultures and mine, was a shock. My goal was to create with the tool we had—WhatsApp—a viable classroom within which I could deliver instruction reaching the same objectives, with similar practices, as I had at our school. Over the course of a week, I did just that. Here, then, is a simple view of how to create a distance learning teaching platform that functions almost as well as a face-to-face classroom.

Twelve Steps to Teaching with WhatsApp for SLIFE

- Download and practice using WhatsApp Web, a browser-based application that enables you to use WhatsApp on a computer or a smartphone. Make sure everyone can use the mic and send features, including reply to a person, rather than the thread at large. (The instructor will want to use a computer to facilitate sending documents, videos or photos.) Unfortunately, WhatsApp does not provide privacy settings at this time (I checked with them) to conceal phone numbers.

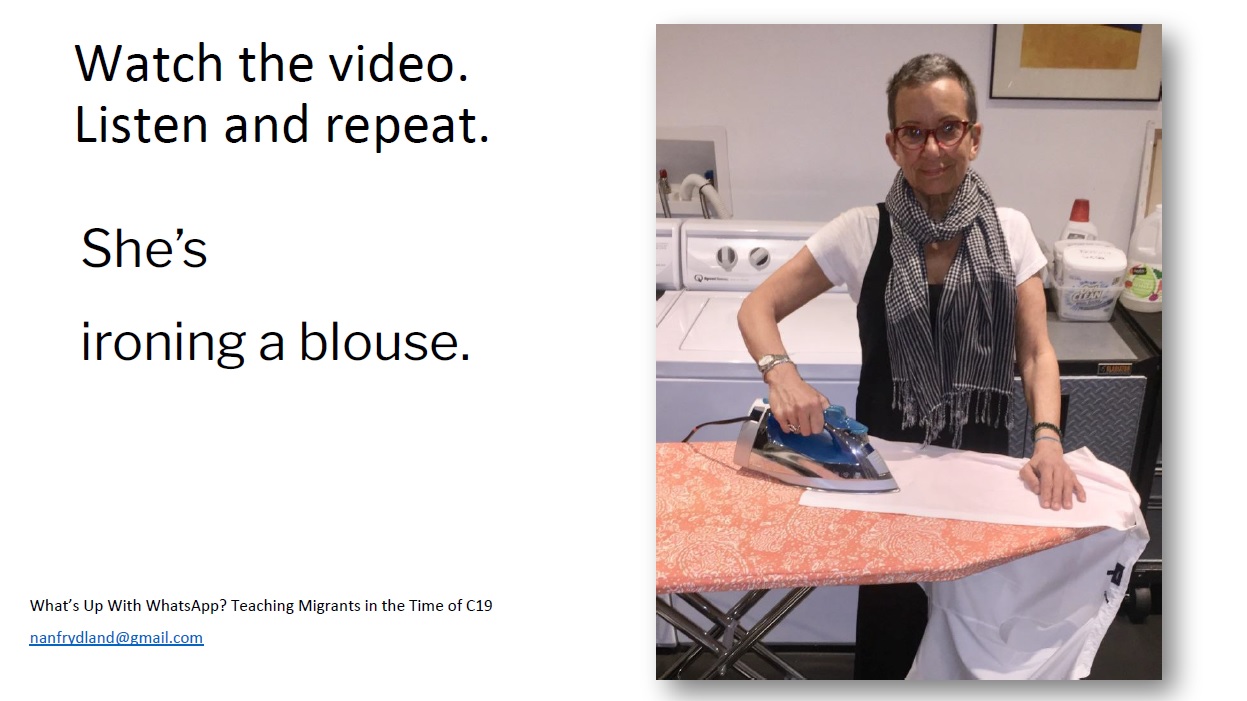

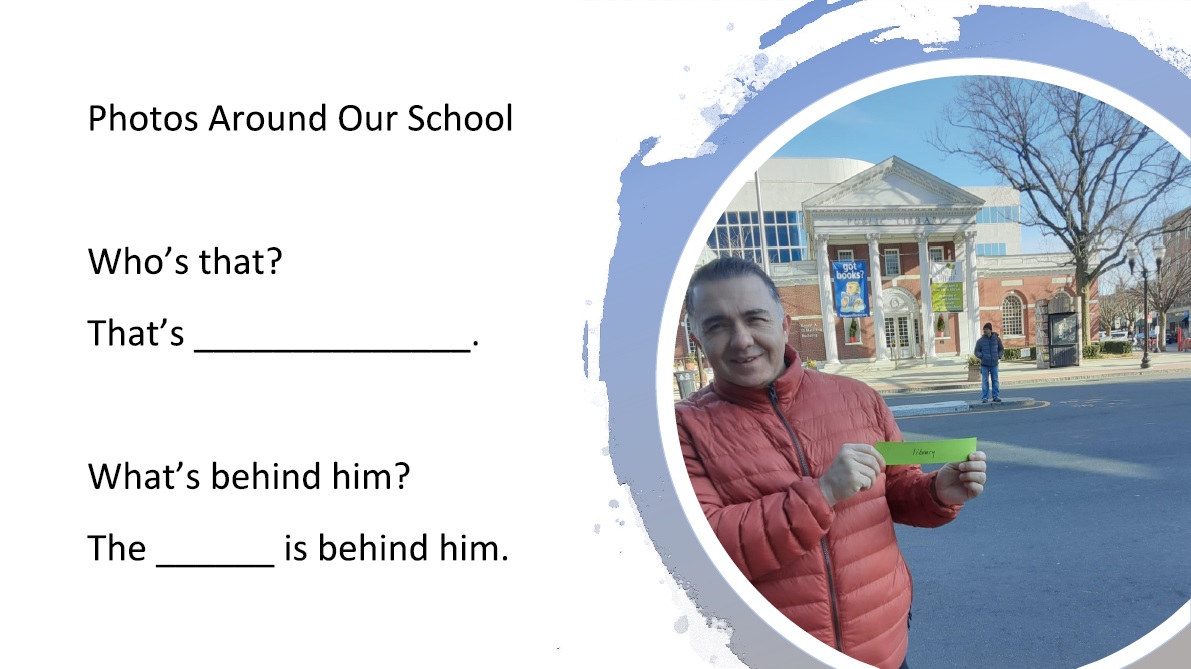

- Create class materials in PowerPoint slides to share through the app. Use large fonts, limited text and large photos. Compose questions that can be answered by short texts or voice messages and tasks that are compatible with the WhatsApp features such as taking a selfie by using the camera feature.

- Increase visual support and input to keep students engaged and scaffold the written component. Make your own lively, instructional videos and keep it simple. For beginners, showing actions around the house like cleaning, reading and working on a computer can be reused accompanied by texts with changing objectives. Have a sense of humor. Some of my videos are posted at “NanTeaches” on Facebook.

- Arrange the slides on one side of your computer screen and WhatsApp on the other. In this way you can copy and paste a slide into the message box of WhatsApp. Send videos first and follow with texts allowing students time to process the video and respond to the texts.

- Reduce the workload of a class session because everything will take longer online: delivering instruction, time for students to process material and respond, the sheer number of individual responses sent to students.

- Scaffold new tasks with familiar language and content. For example, repurpose photos and text from previous lessons to reduce cognitive load. The best visuals are realistic color photos. Many SLIFE have trouble deciphering black and white pictures and most cartoon drawings.

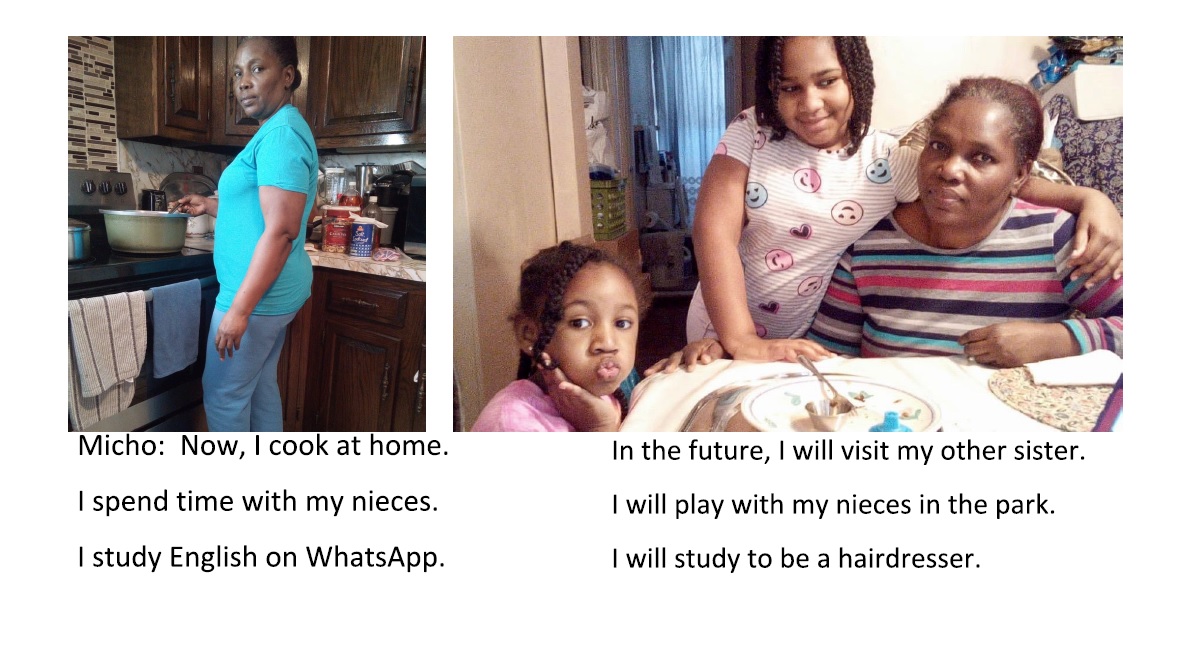

- Keep the focus on your objectives and curriculum but be flexible. For SLIFE, immediate relevance is essential. Here’s an example: What did you do before the pandemic? What are you doing now? What are you going to do in September? Students use three tenses to name three things for each category. The teacher organizes the response in a chart and then asks questions about that data. This could be done with photos as well as text. Most of my students focused on how they are spending time with family now, playing, cooking, and studying. They couldn’t do that before, when they were working and going to school.

- Assign homework that includes activities beyond reading and writing, especially in developing technological skills, such as taking and sending photos and videos with captions.

- Provide office hours for students to chat privately, get tutoring, or review homework. I made an hour after each class available, and students rarely used it.

- Expect technology to fail sometimes. Overtime you can start to anticipate bugs or outages and be prepared for them. Know how to conduct class solely with your phone if your computer connection fails.

- Integrate information about COVID-19, local services such as food pantry availability, free mask distribution, and CDC guidelines, with your regular lesson planning.

- Print and mail copies of materials to support online work. My students do not have access to PowerPoint or printers, so I am printing copies and mailing them to their homes. We have always co-created our own loose-leaf binder books, so they will be able to file these lessons with the others.

Fostering Connection in the Digital Classroom

It is a reflection of the resiliency and persistence of my students that they have attended classes, some without missing a minute, since March 16. We have remained connected emotionally and intellectually. We have adapted to changing circumstances as all of us have at some point in our lives and we have discovered new ways of learning and being. For many students, the visual orientation of the WhatsApp classroom is very appealing. As a teacher who has long advocated for original materials, designing slides and making videos has given me a new way to engage with students that is personally appealing. Because I haven’t been copying these materials, I haven’t had to worry about that cost, or the time to copy them. But I finally decided that providing copies of the slides to students would be useful, so I’m going to do that. The final benefit of our distance learning is that oddly, it feels more culturally consistent with oral cultures than our print-based classroom. Although we’re not face-to-face, we are using speaking and listening at least as much as reading and writing. For this reason, it appeals to many students from collectivist cultures who may have limited or interrupted formal education.

Teaching as Learning

This experience brought me back to 2003, when I was a middle-aged college student and my friend Marcia asked me if I wanted to teach ESL classes at night. It was an emergency situation, she said. A teacher had left in the middle of the school year and no one could survive on the pay. I spent winter break reading “Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Language” by Marianne Celce-Murcia. I picked my pedagogy (Freirean), chose methodology (project-based), and drafted the outline of a curriculum. I was a self-taught teacher for the next ten years, just as now, I’m a self-taught online instructor, motivated by the urgency of serving deserving learners. Then, as now, it’s just the beginning of what I suspect will be an exciting journey into a new realm of learning. This time, it’s called Integrating Digital Literacy into English Language Instruction. I believe that learners will benefit deeply.

3 Comments.

This is good to think about the hurdles that need to be overcome in these covid times.

Excellent thanks, Nan.

Beneficial