By Jayme Adelson Goldstein of Lighthearted Learning

Over the past 11 months, teachers’ experiences in the virtual learning environment have ranged from sublime to frustrating to exciting to decidedly unexciting. Just last week on a particularly frustrating day, I lost my Internet connection three times while providing PD and switched from phone hub to delivering via phone to crying quietly offline. It went back on, we made it through, but this situation is not unusual in the least and tests our (and our learners’) flexible thinking and problem-solving skills regularly.

It’s true that there have been many barriers to engaging learners in our virtual classes:

- equitable access (e.g., access to WIFI, devices, cellular data, and peripherals),

- limited digital skills (for learners and instructors), and

- and the heightened pandemic priorities of family, work, and healthcare.

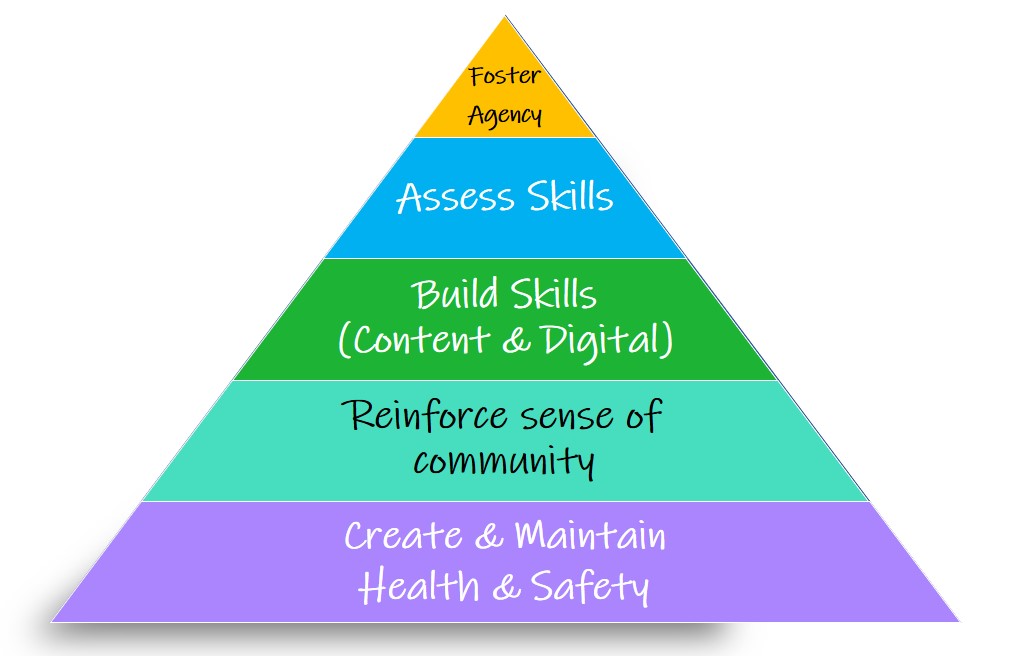

In talking with teachers about instruction, I’ve recognized a deep sense of loss in their anecdotes. Some of this is based in loss of identity—where before they had felt expert in meeting their learners’ needs, now they are questioning the quality of their teaching and the value of the virtual learning experience. When I first came C2C (camera-to-camera) with my colleagues’ concerns, I immediately thought of Maslow. And then, because I’m just that audacious– I created my own Maslowegian Pandemic Pyramid for the Adult Classroom:

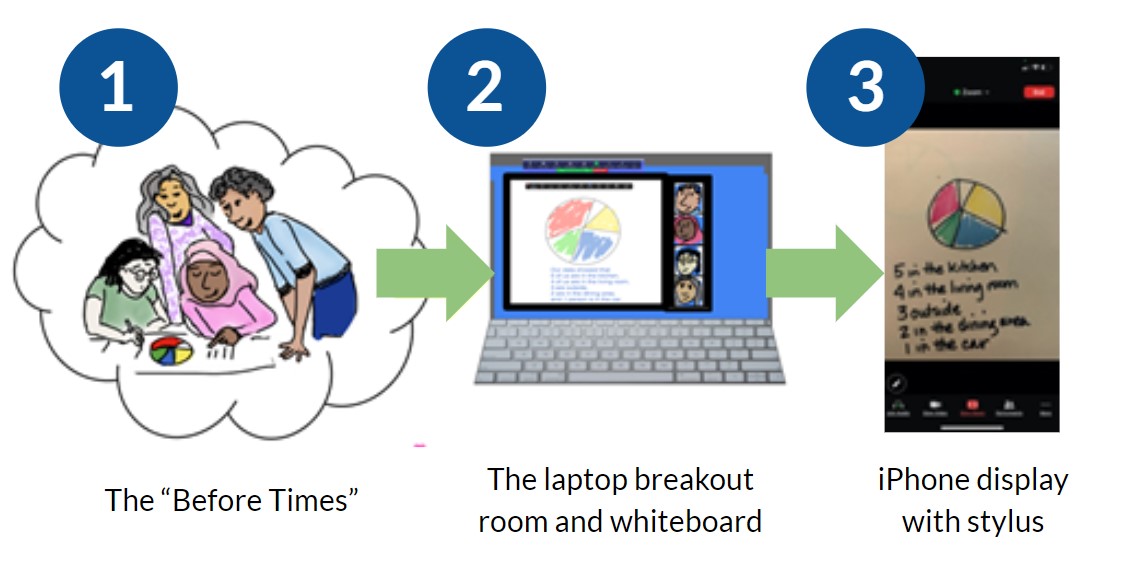

As proud as I was of the pyramid, sharing it with instructors didn’t address the heart of the issue—teachers’ sense that prior to March of 2020 they had been providing rigorous, relevant, and engaging instruction and now, in this new environment, they were not. This led me to wonder if it might be helpful to focus on exactly what teachers were doing so well in the “before times” and find a way to help them transfer those practices to the virtual learning environment (VLE).

The pre-pandemic technology integration models offered some insights. Two models in particular, SAMR and TECH, were helpful. (See Ruben Puentedura speak about his SAMR model and Jen Robert’s introduce her TECH model.) These models were developed to help teachers determine how to intentionally enhance face-to-face (F2F) learning with digital tools and processes. The substitution level of these models is characterized by having learners use digital tools, tasks and processes that imitate classroom tools or processes, (e.g., using a keyboard instead of a pencil). Although substitution was often perceived as the bottom rung of the integration ladder and was not as highly lauded as levels where learners co-construct their learning using new technologies and skills, both Puentedura and Roberts have stated that the substitution level can still be a powerful place from which to teach and learn.

Thanks to my colleague, Radmila Popovic, I prefer the term effective practices to best practices. Effective acknowledges that different practices may be more valuable in different contexts. These days, however, I’ve started using the term sustaining practices – those instructional strategies and tasks that sustain learning in both the F2F and virtual classroom by integrating adult learning principles, being research-based, and crossing content areas, levels of proficiency and modes of learning. In other words, the basis of our 21st century instructional repertoire.

With the sustaining practices and substitution levels in mind, I started working on a Digital Substitution chart, determining teachers and learners can make use of readily available features and tools on platforms such as Zoom. Also, because I had seen that teachers and learners alike were confounded by the different experiences on phones and computers, (let’s just start with the size of the screen!), I knew that the chart had to help teachers envision the learner’s perspective on a smartphone.

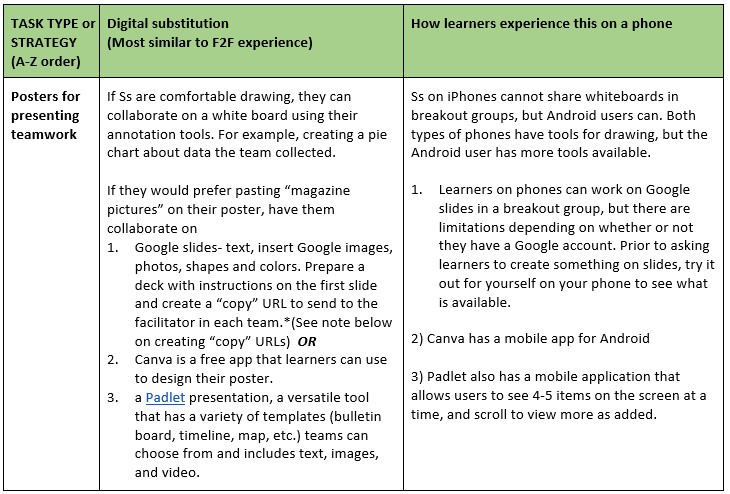

The example below shows the organization of the chart.

Many of the transfers in the chart may seem obvious, e.g., having a team create a poster with a chart to help them visualize and present data can be done by having teams work on a whiteboard in breakout rooms. However, what is less obvious is how they might play out with a group of students participating via different devices. Image (3) below illustrates how learners in a Zoom class on iPhones would have to write on the screen with their finger or a stylus because there is no text tool on their annotation menu. And, if there were no Android users in the team, the learners on iPhones would not be able to share a whiteboard, but would, instead, have to share a photo of a piece of blank paper to use as their whiteboard.

Another consideration is the length of time it takes for learners on phones to complete a process versus learners on laptops or desktops. To get that photo for the whiteboard (the first time) they would need to take a photo, save it, hit share screen, give zoom permission to access their photo roll, select the photo to share, and then share it. None of that is beyond our learners’ abilities—but it does take more time than clicking Share screen > Share whiteboard. The chart mentions these time considerations as needed.

The chart focuses on the sustaining practices, but ideally, as we think about the transfer of F2F to virtual instruction we want to include the shifts we were making from sustaining to high-leverage practices—deepening learning by:

- including scaffolds to help learners tackle challenging content

- engaging critical thinking and making use of structured collaboration

- prompting learners to use academic language, and

- fostering learner agency- learners’ voice and choice.

Happily, none of these elements are dependent on being F2F and we can begin incorporating them alongside any of the tasks and strategies we transfer to our virtual classes.

The Digital Substitution Chart is licensed under creative commons for attribution and share and share alike. I and my colleagues, Lori Howard and Sylvia Ramirez, welcome any comments with suggestions for additions and revisions. We gratefully acknowledge all contributions on the last page of the document.

To learn more about the Digital Substitutions Chart, check out Jayme’s lightning talk (starting at the 27:17 mark) from our February 12, 2021 Distance Education Strategy Session.