By Jennifer Maddrell, Jen Vanek, and Justine Schade

As described on our project home page, EdTech Maker Spaces (ETMS) are service-learning opportunities for adult educators that incorporate both professional development and the crowdsourced curation and creation of free and open educational resources (OERs) aligned with Teaching Skills That Matter (TSTM). In this blog post, we consider the characteristics and foundations of service learning as an educational approach and share the methods we use to integrate service learning into the ETMS design and facilitation.

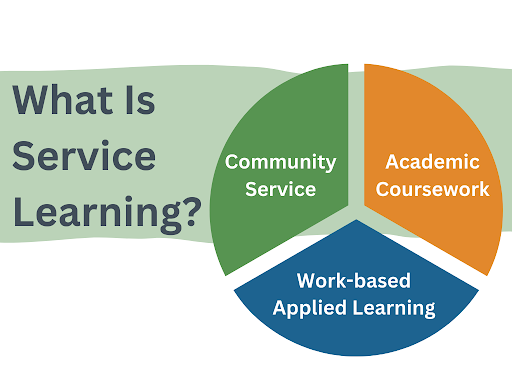

What is service learning? Why is it effective?

Service learning blends volunteer community service, academic coursework, and applied work-based experiences (Bringle & Hatcher, 1996; Furco, 1996). A central service-learning goal is facilitating meaningful experiences for the learner and benefiting others (Pritchard, 2002). These goals have been realized in numerous past national initiatives, including the Campus Compact in 1985, the National and Community Service Act of 1990, and the National Service Trust Act of 1993.

Reviews of theory, research, and practice focused mostly on higher education suggest that service learning promotes effective participant engagement with the subject matter and positively affects academic achievements and other personal and social outcomes (Yorio & Ye, 2012). Further, studies suggest benefits for the served community organizations, including added labor to fulfill their missions and access to resources (Blouin & Perry, 2009). This evidence grounds our belief in the value of service learning as a professional learning strategy and supports the design and facilitation of our ETMS experiences.

Experiential Learning: The Foundation of ETMS Experiences

Service learning is often linked to the experiential learning philosophy promoted by John Dewey, which emphasizes learner inquiry, experimentalism, reflection, citizenship, community, and democracy (Giles & Eyler, 1994). Being built on this foundation of experiential learning, the EdTech Maker Space achieves two aims:

- Community Service: Our volunteer Makers curate and create OER to benefit adult learners in civics education, digital literacy, financial literacy, health literacy, and workforce preparation.

- Learning: Our Makers gain knowledge and skills to find, evaluate, and adapt/create digital learning activities using various resources and educational technologies during their service experiences.

Situated Learning: The ETMS Approach to Facilitation

Our ETMS facilitation is grounded in the theory of situated learning, which holds that learning happens when people are engaged in the social process of discovery and collaboration in problem-solving (Lave & Wenger, 1991). The theory advances three approaches: problem-based learning, communities of practice, and cognitive apprenticeships.

Problem-Based Learning

Problem-based learning environments incorporate 1) a meaningful question or challenge, 2) learning goals focused on gaining relevant knowledge and skills, 3) an opportunity to practice those skills, 4) engagement in collaborative activities, 5) incorporation of learning technologies, and 6) creation of a tangible product addressing the driving question or challenge (Krajcik & Shin, 2022, p. 75). We create the context for Makers to be part of an authentic “design as problem-solving process” (Jonassen, 2008). Makers focus on developing the knowledge and skills that they need to make technology integration and instructional design decisions to best support teaching and learning (Saubern et al., 2020; Vanek, 2022; Wilson et al., 2020).

Makers in our service-learning experiences are challenged with applying various real-world educational practices, such as identifying, organizing, evaluating, adapting, or creating learning activities for adult learners. Makers learn about and use relevant EdTech tools and best practices as they collaborate with others to complete design challenges.

Collaboration in Communities of Practice

To facilitate our collaborative service-learning approach, we create various online “communities of practice.” In these online spaces, participants experience the “interdependence among the learner, activity, knowledge, and the world” (Lave, 1991, p. 81). While Makers work independently on most of their assigned tasks, we include opportunities for peer-to-peer collaboration, feedback, and strategy sharing in whole-group and small-group breakouts during our live webinar sessions (e.g., Design Slams and virtual Office Hours). Makers connect with facilitators and each other using Google Classroom, our asynchronous learning management system. They also have access to an online forum where they can share ideas with each other. We extend the reach of our work to the public during online showcases where Makers highlight the outcomes of their collective efforts.

Cognitive Apprenticeship Facilitation

The “cognitive apprenticeship” theory suggests that learners benefit when an expert makes their knowledge visible for learners to observe. Our guided participation approach promotes the development of teacher expertise through the use of various cognitive apprenticeship methods, including 1) modeling, 2) coaching, 3) scaffolding, 4) reflection, and 5) exploration (Collins & Kapur, 2022). Our facilitation team includes subject matter experts in adult education and instructional design who present and model best practices associated with the Makers’ design challenges. Facilitators provide support as Makers tackle their assigned tasks, including scheduled office hours and asynchronous support resources in Google Classroom. Small-group break-out sessions and Maker showcases allow reflection on their process, successes, and challenges.

Who Benefits from our ETMS Work?

ETMS service learning is central to our Teaching Skills That Matter – SkillBlox research initiative. Our early research suggested that teachers needed more resources to support their TSTM-aligned instruction, yet they struggled to find the time and expertise they needed to create learning activities on their own. Through ETMS service-learning, educators gain valuable skills and knowledge to leverage in their future work and contribute to the body of open and free resources available to all teachers seeking to integrate TSTM into their instruction.

References

Blouin, D. D., & Perry, E. M. (2009). Whom does service learning really serve? Community-based organizations’ perspectives on service learning. Teaching Sociology, 37(2), 120–135. http://tso.sagepub.com/content/37/2/120.short

Bringle, R. G., & Hatcher, J. A. (1996). Implementing service learning in higher education. The Journal of Higher Education, 67(2), 221–239. https://doi.org/10.2307/2943981

Collins, A., & Kapur, M. (2022). Cognitive Apprenticeship. In R. K. Sawyer (Ed.), The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences (3rd ed., pp. 156–174). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108888295.010

Furco, A. (1996). Service-learning: A balanced approach to experiential education. Expanding Boundaries: Serving and Learning, 1, 1–6.

Giles, D. E., & Eyler, J. (1994). The theoretical roots of service-learning in John Dewey: Toward a theory of service-learning. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 1(1), 77–85. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.3239521.0001.109

Jonassen, D. (2008). Instructional design as design problem solving: An iterative process. Educational Technology, 48(3), 21–26. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44429574

Krajcik, J. S., & Shin, N. (2022). Project-based learning. In R. K. Sawyer (Ed.), The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences (3rd ed., pp. 72–92). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108888295.006

Lave, J. (1991). Situating learning in communities of practice. In L. B. Resnick, J. M. Levine, & S. D. Teasley (Eds.), Perspectives on Socially Shared Cognition (pp. 63–82). American Psychological Association.

Lave, J. & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

Pritchard, I. (2002). Community service and service-learning in America: The state of the art. In A. Furco & S. Billig (Eds.), Service-Learning: The Essence of the Pedagogy. IAP.

Saubern, R., Henderson, M., Heinrich, E., & Redmond, P. (2020). TPACK–time to reboot? Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 36(3), 1–9.

Vanek, J. (2022). Supporting quality instruction: Building teacher capacity as instructional designers. Adult Literacy Education, 4(1), 43–49. https://doi.org/10.35847/JVanek.4.1.43

Wilson, M. L., Ritzhaupt, A. D., & Cheng, L. (2020). The impact of teacher education courses for technology integration on pre-service teacher knowledge: A meta-analysis study. Computers & Education, 156, 103941. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.103941

Yorio, P. L., & Ye, F. (2012). A meta-analysis on the effects of service-learning on the social, personal, and cognitive outcomes of learning. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 11(1), 9–27.https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2010.0072

2 Comments. Leave new

Reading this has awakened me to a new reality, the reality of a new language in teacher training, lesson delivery and community engagement.

Thanks for reading & responding, Theodore!