By Rachel Riggs and Zoe Reinecke

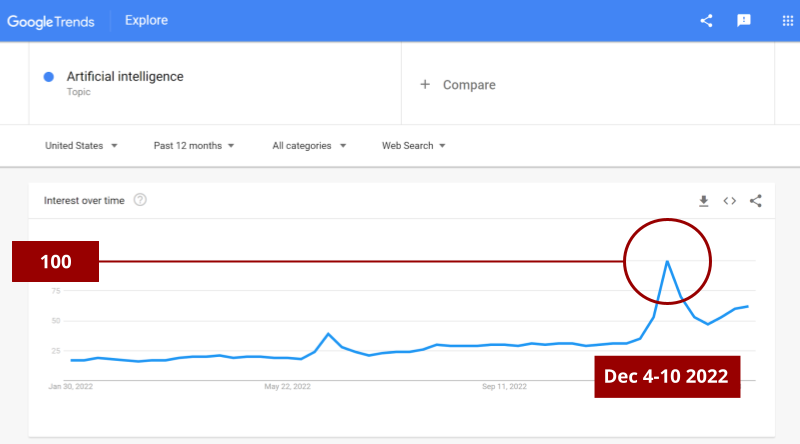

You’ve likely heard a lot of recent chatter about Artificial Intelligence (AI). You may have even tried out some of the new AI tools. You wouldn’t be alone. There’s no lack of blog posts, articles, infographics, and the like, on the topic of AI, including ChatGPT, an impressively conversational new chatbot. Look at how interest in the topic of Artificial Intelligence peaked in popularity in the U.S. over the last year around mid-December, coinciding with the launch of ChatGPT on November 30th.

However, the complexity of AI in edtech up to this point has been highly technical and not exactly “classroom-ready” for most educators. Furthermore, we know that the way AI impacts K12 and higher education classrooms will look different in the context of adult education. In many ways, adult education is the Wild West of edtech (depending on where you teach, of course). Generally speaking, we don’t benefit from the same security measures or wealth of IT resources that can be seen in public school systems and universities, making edtech in adult education somewhat precarious and always fun.

So, welcome to the Wild West, let’s see how we can navigate AI together.

Defining AI and Ways You’re (Probably) Already Using It

AI is a class of technology that identifies patterns in data and applies these patterns to perform tasks in a manner that emulates human intelligence. AI has enabled computers to find solutions to problems thought to be unique within the domain of human intelligence. For example, Google Translate uses AI to identify the best translation based on the broader context of the given prose. The performance of AI technologies like Google Translate uses machine learning to improve over time. In education, machine learning is fundamental in applications such as Mathia, a math tutoring software. The individualized tutoring provided to learners by Mathia is improved over time as the software refines its understanding of their needs.

In addition to Google Translate and learning apps, you’ve probably seen AI at work in some of your most basic day-to-day tasks. Do you use Face ID on an Apple iPhone? Does your email server predict the next few words that you’re going to say as you’re typing? On the weekend, does Alexa turn on your favorite playlist? These are just a few of the ways that we’re already using AI in everyday life. I asked some colleagues at World Education how they interacted with AI back in November and here’s what they said:

Victoria Neff uses the formulas that Google recommends when she’s working on a spreadsheet.

Jeff Goumas lets Google’s AI finish his sentences when he’s composing emails in Gmail.

Jamie Harris has been seeing AI-generated art on her social media feeds. You know, the ones that look like this?

Rachel Riggs was introduced to Padlet’s “I can’t draw” by Jayme Adelson Goldstein in a recent EdTech Maker Space.

The Important, the Bad, and the Ugly

While some school districts are looking for ways to ban AI and developers are coming up with technologies to detect students’ AI use, other educators argue these aren’t viable strategies and harm our relationships with students. The history of edtech, from the projector to the web to the Wikis, Open Education Resources (OER), Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), and Mobile Learning (mLearning), gives us a basis from which to predict how AI will impact education and it can be encouraging to see how far we’ve come. Like the introduction of any new technology, instead of attempting to block or limit use, we need to understand AI’s potential benefits to teachers and students, as well as its risks, in order to guide its inevitable use in adult education.

Analyzing these benefits and drawbacks at this early stage should be a shared process where everyone has a voice and the topic is addressed with a balanced approach. Programs need to provide a space for staff to share knowledge, strategies, and considerations. Teachers need to be aware of the legitimate concerns around these tools. Learners must be involved in experimenting with new technology in an educational setting where they can engage in critical conversations about AI’s impact. These critical conversations should include:

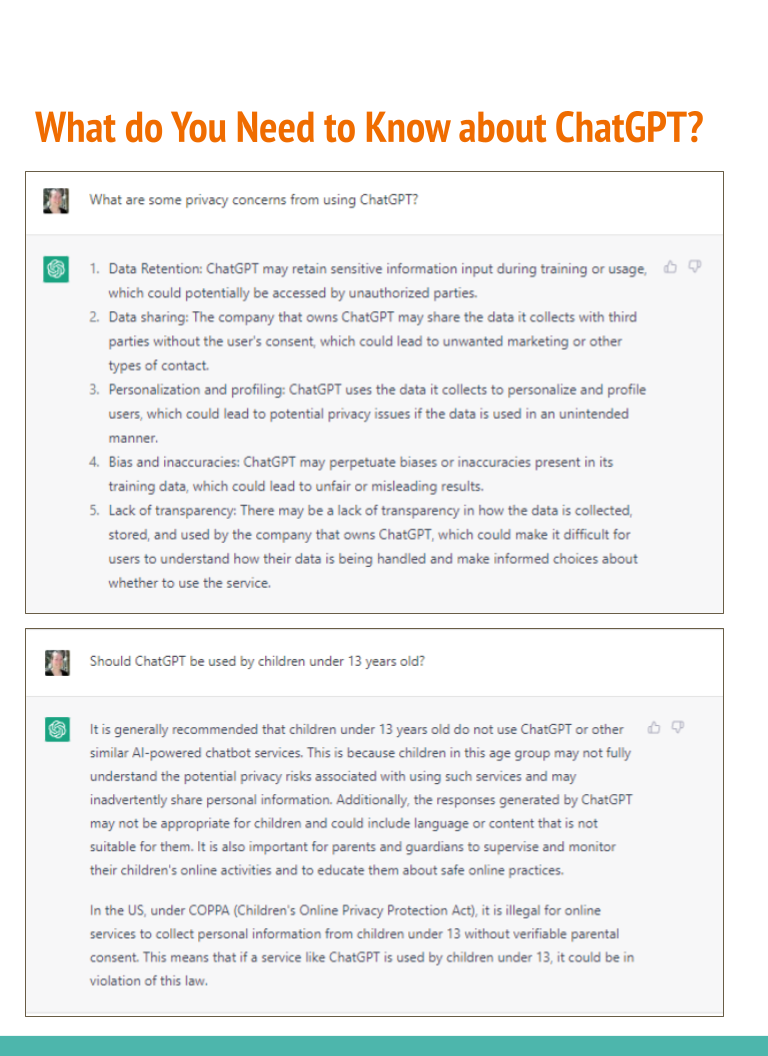

- Data / Privacy Concerns

When I created the impressionist image of myself to give an example of AI-generated images (or avatars) on social media, the experience was a little unnerving and gave me firsthand experience with cautionary information that others have shared. In order to generate the avatars, you have to share 10-20 photos of yourself and you’ll see a message before you select the photos stating, “🔒 Photos will be immediately deleted from our servers after the Avatars are ready”. According to the Privacy Policy, the images I shared with the app are held on Lensa’s servers and used to train an AI model. While the images are purportedly removed from the servers right away, there’s a lot of other information that Lensa is gathering about me when I download and use the application.

According to the Privacy Policy, the images I shared with the app are held on Lensa’s servers and used to train an AI model. While the images are purportedly removed from the servers right away, there’s a lot of other information that Lensa is gathering about me when I download and use the application. - Lack of Diversity / Cultural Representation

Did you notice anything about the Padlet example I shared earlier? I asked for a “teacher” and the results were all women of a seemingly similar age. Check out what happened when I searched for a “tech geek”. Do you notice anything? In my prompt, I didn’t give any information about what the “tech geek” should look like. In fact, I entered the prompt with myself in mind, a white woman in her early 30s who wears contacts, not glasses. Rather than generating a diverse set of tech geeks, the results reflect that this AI model has a limited idea of what a tech geek looks like.

What we must remember is that these systems are trained on data sets that may come from biased human perspectives and/or historical inequities. In other words, machines are learning from the “ugly” of humanity. But, they’re not just learning the ugly and reflecting it back to us, they may be making the problem worse by, as the Harvard Business Review puts it, “baking in and deploying biases at scale in sensitive application areas”. In Padlet this may seem low stakes but when AI algorithms are used in criminal justice or hiring practices, the unintended consequences are chilling.

- Outdated Information

ChatGPT is a very honest liar. What I mean by that is that it will openly tell you that its data set is limited to 2021 and earlier (so it can’t give updated, current information). It’ll also pretty much tell you that it lies (see image). In this way, ChatGPT is similar to my four-year-old, who is not allowed to talk to ChatGPT, per ChatGPT’s own recommendation.

Image from Chat GPT & Education by Torrey Trust, Ph.D.

In an educational setting, it’s challenging to introduce subjects that are new to us, in which we can’t offer expertise. Technology, however, can be a great equalizer. It evolves rapidly and, as we all experienced during the pandemic, forces educators to “learn as they go”. While it’s not a comfortable position to be in, be encouraged that when you bring new technology to the classroom, facilitate critical discussion about it, and pique curiosity and awareness of what’s to come, you are embedding digital resilience in your practice, preparing adult learners to navigate the ever-changing landscape of technology.

Read Part 2 of this blog series “A Balanced Approach” to explore activities and conversations that will help you bring artificial intelligence to the classroom.