By Naila Bairamova and Crystal Dixson

This blog post is the first in a two-part series that focuses on barriers to learner participation and persistence in employer-supported educational opportunities. In this framing of past research and reports, the 21 CLEO Research team draws on Margaret Patterson’s categories of learning and persistence barriers as an analytic lens to situate literature reviewed in our landscape scan. In this post we focus on external situational barriers (deterrents that arise as adults attempt to balance multiple roles in their lives or deal with health conditions) and institutional barriers (result of educational or employment policies and practices which prevent participation).

Current high-employment levels in the US have prompted employers to offer work-based education and training opportunities that offer a variety of learning opportunities for working learners. Simply offering diverse opportunities for working learners to fill skills gaps does not mean that learners will participate in them. In order to understand why a working learner does or does not take part in these opportunities, we need to look at the learning ecosystem around the working learners, including the barriers inhibiting their participation in learning opportunities. The very resources that can help learners address these barriers have the potential to become a robust support mechanism driving working learners to successful career and personal growth. Getting to the Finish Line, a report conducted by the Institute for Women’s Policy Research, found that the probability of completion of the educational opportunity increased by 11% per one supportive service that addressed one of the barriers that working learners faced.

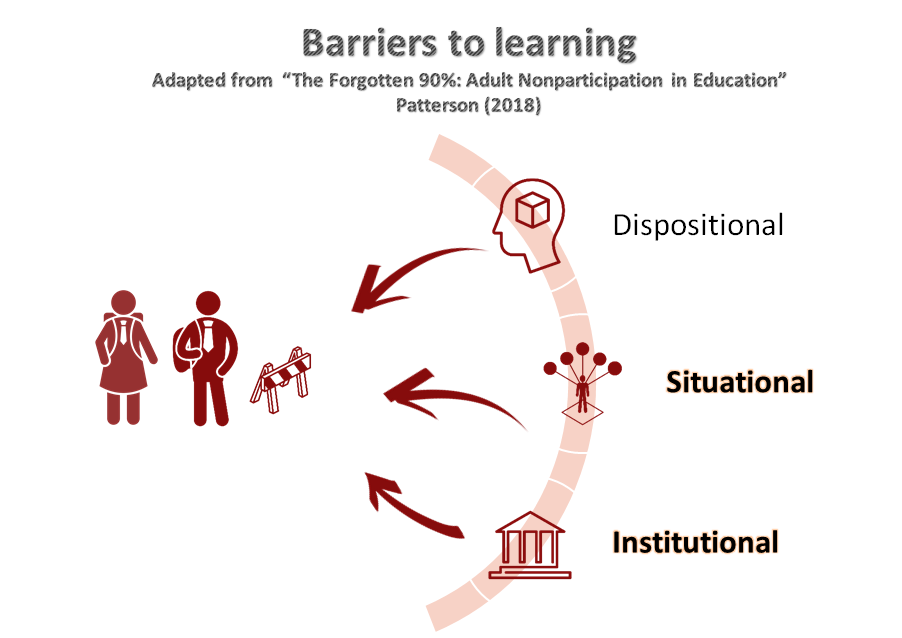

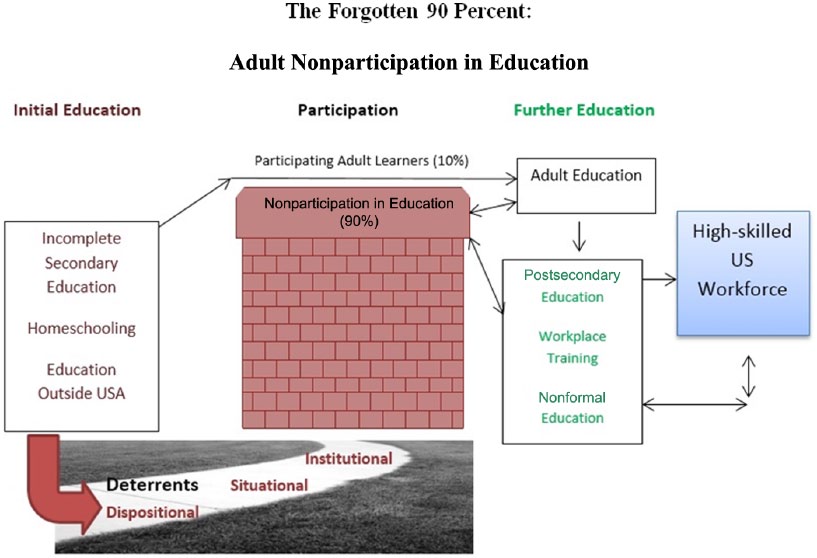

To begin to understand what such support might entail, we first need to define the barriers. Margaret Patterson, in the article The Forgotten 90%: Adult Nonparticipation in Education, neatly frames these to include a combination of situational, institutional, and dispositional factors. We draw on Patterson’s categories as an analytic lens used to organize other literature reviewed in our landscape scan.

Situational barriers are deterrents that arise as adults attempt to balance multiple roles in their lives or deal with health conditions. Institutional barriers are the result of educational or employment policies and practices which prevent participation. Dispositional barriers occur when the learner lacks confidence in their skills and abilities, or when they are unaware of their career options. For this post, we will focus on situational and institutional barriers. We will discuss dispositional barriers in more detail in our next post. We grouped situational and institutional barriers because they are largely external to the learner, while dispositional types of barriers reside within the learner.

Institutional barriers

Lack of Support. The Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies, or PIAAC, was a large-scale study that assessed the literacy, numeracy, and technology-related skills of adult learners worldwide. The report, Adult Transitions to Learning in the USA: What Do PIAAC Survey Results Tell Us?, places the findings from the PIAAC surveys into context. An importing finding included in the report states that US adults scored below the international average on literacy, numeracy, and technology-related skills, and those scores varied considerably based on educational background. Not only were skills low, but learners working to acquire basic literacy skills reported not always receiving adequate support from their employers, such as providing release time for studying, tuition assistance, or paid study time. Nearly 90% of surveyed adults who had a high school diploma and who were involved in formal learning situations reported studying outside work, and many of them had a hard time getting release time from work to do so. In contrast, adults with some post-secondary education had twice as much release from work time for formal education than adults with a high school diploma.

Costs of Education. Adult learners surveyed by PIAAC identified cost as one of the major barriers to learning, especially for formal learning. The issue is exacerbated by the fact that working learners may lack financial literacy skills like knowing how to apply for benefits, financial aid programs, and so on. In Getting to the Finish Line, 27% of men and 23% of women identified financial education as an unmet need. The cost of stable childcare is another barrier to learning, especially for female workers. Advancing Frontline Women: Realizing the Full Potential of the Retail Workforce states that women are more likely to be faced with balancing family and caregiving responsibilities. In fact, 34% of women aged 18–24 reported a lack of access to stable childcare as their primary obstacle to finding a job, and 26% struggled to balance childcare and work.

Immediate Supervisors. Another institutional barrier working learners face is the lack of support from immediate supervisors. Frontline managers are closest to frontline workers and are in the best position to assist in their development and engagement with the company. Many frontline managers have conflicting job responsibilities and are not given the needed training or human resources support to assist in coaching and skills development for frontline workers. Additionally, frontline managers often are not held accountable or provided with incentives to promote employer provided learning opportunities and encourage the frontline workers to take advantage of them.

According to Developing America’s Frontline Workers, a report put together by the Institute for Corporate Productivity, many organizations do not measure supervisor effectiveness at developing frontline workers. Furthermore, of the organizations that do measure supervisor effectiveness, the most popular measurements are frontline worker retention and individual productivity improvements. However, only two measurements have been found to correlate with market performance, that is an index calculated by averaging responses about companies’ revenue growth, market share, profitability, and customer satisfaction over time. The two measurements are:

- the number of workers taking advantage of tuition assistance, and

- the number of workers advancing to higher-skilled and higher paid positions.

High market performing organizations are 2.5 times more likely to reward frontline managers who encourage the development of frontline workers with compensation or a promotion.

Situational barriers

Working adults are often confronted with significant barriers to participating in learning opportunities as they juggle multiple responsibilities and family obligations. When surveyed, working adults expressed concerns about transportation, family needs, and financial constraints.

Transportation. In the article Critiquing Adult Participation in Education, Report 1: Deterrents and Solutions, transportation is cited as one of the largest concerns among adult workers. Depending on the worker’s location and mode of transport, commuting can take a significant amount of time, which reduces the amount available for study. The reliance on public transportation, carpools, as well as the high cost of vehicle maintenance and fuel all contribute to non-participation in education. This overlaps with numerous family responsibilities and financial hurdles.

English Language and Literacy. English language proficiency is a barrier faced by working learners in the US whose first language is not English. English Language Learners (ELLs) face prejudice and mistrust because of their limited linguistic proficiency. They experience communication barriers and thus tend not to participate in educational opportunities. According to The Forgotten 90%: Adult Nonparticipation in Education, only 10% of adult workers who face these barriers pursue educational opportunities, while the remaining 90% do not. Patterson and Paulson (2015) report that the PIAAC data show that, among adults without a high school diploma who did not participate in any educational opportunities 12 months prior to the survey, 9.5 million do not read or write in English well or at all.

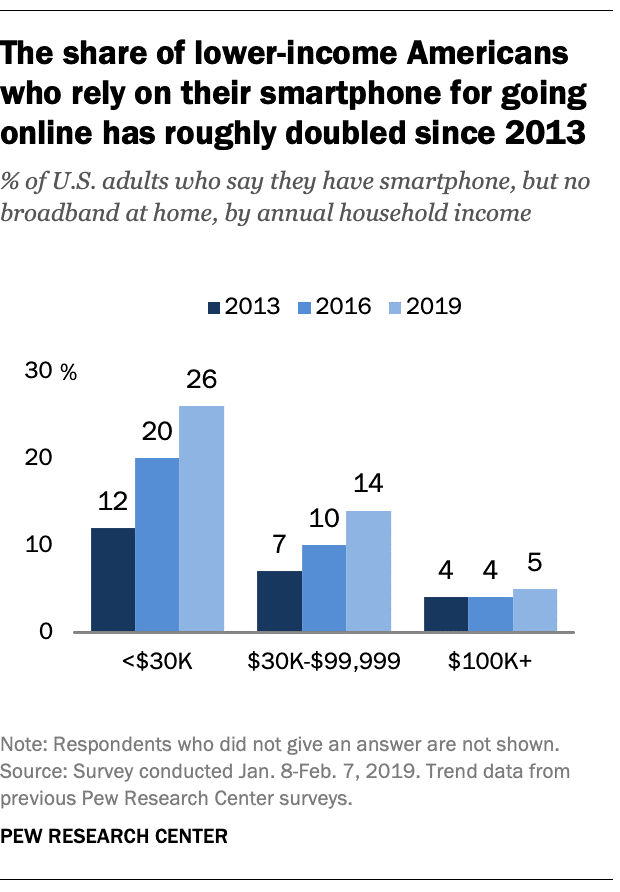

Digital Inequity. Technological barriers and inequities also can hinder working learners’ participation in both formal and informal educational opportunities. These barriers are manifested in different ways. First, the lack of basic digital literacy skills can prevent participation in opportunities that are connected with technology or online learning. According to the findings in Stats In Brief: A Description of U.S. Adults Who Are Not Digitally Literate, Americans with low digital literacy skills are likely to be adults working low-skilled jobs with limited education, or foreign born. About 41% of adults without a high school diploma are not digitally literate compared to 17% of adults who earned a high school diploma, and 5% of adults with some post-secondary education. Another form of technological barrier, according to Digital Inequalities and Why They Matter, is the lack of information literacy and the inability to navigate the vast amount of information available on the Internet. Finally, even though Internet use has grown steadily among all populations, digital inequality can be found in the medium through which Internet access is received. According to a recent Pew Research Center Internet/Broadband Factsheet, low-income Americans are more likely to be smartphone dependent. This poses challenges because, for many learning activities, adequate space to type, view and explore content is essential. Moreover, mobile data usage is often restricted or expensive on smartphones.

Digital inequality is an issue that impacts learners of all ages in the United States, even younger learners who are often assumed to have more technological proficiency. According to Pew Research Center Internet/Broadband Factsheet, only 46% of adults who do not have a high school diploma and 56% of low-income households have broadband Internet access. Broadband access is high-speed Internet access that is always on and faster than the traditional dial-up access. Learning through a smartphone can be problematic for many reasons, including the fact that not all websites are mobile-friendly. Moreover, word processing for formal learning using a smartphone is challenging and accrues a significant disadvantage to those who depend on smartphones and expensive cellular data for access to the internet.

Digital inequality is an issue that impacts learners of all ages in the United States, even younger learners who are often assumed to have more technological proficiency. According to Pew Research Center Internet/Broadband Factsheet, only 46% of adults who do not have a high school diploma and 56% of low-income households have broadband Internet access. Broadband access is high-speed Internet access that is always on and faster than the traditional dial-up access. Learning through a smartphone can be problematic for many reasons, including the fact that not all websites are mobile-friendly. Moreover, word processing for formal learning using a smartphone is challenging and accrues a significant disadvantage to those who depend on smartphones and expensive cellular data for access to the internet.

Impact of External Barriers

When considering the potential positive impact of workplace or employer supported learning, It is important to consider each of these external barriers, how they interact with each other and with the dispositional barriers that we will unpack in our next blog post. By addressing any of these barriers, employers, education providers, and policy makers can work toward solutions that will improve the likelihood that a working learner will participate and persist. The list of barriers we have discussed in this post is not comprehensive. If you have experience with or knowledge of other barriers, please contact us at 21cleo@pdx.edu or leave a comment below.