The IDEAL Consortium is dedicated to helping member states across the US establish quality, innovative distance and blended learning programs; IDEAL has served as a facilitator of collaboration and sharing of effective practice since its inception in 2002.

IDEAL’s Distance and Blended Learning Handbook addresses both administrative and instructional issues at the core of successful blended and distance education programming. The Handbook is informed by current research, policy guidelines, and observations of effective practice documented by IDEAL Consortium members, past and present, and affiliated state leaders. The Handbook includes collective wisdom of these stakeholders in order to understand how to best leverage recent technological innovations for the benefit of adult education learners. The Handbook does this by presenting content in chapters that address important programmatic considerations.

This three-part blog series began with “Setting the Stage”, which provided historical and policy contexts. In this post, we introduce the importance of developing strong recruitment, screening and orientation practices in your distance and blended learning programs. Look for our final post on instruction and assessment in the weeks to come.

Early research literature on distance learning in adult education in the US first illustrated the importance of finding the right students and setting them up correctly if programs were to succeed in offering distance education (Petty & Johnston, 2002; Askov, Johnston, Petty & Young, 2003; Petty, 2005). A strong start is still understood to be a key initial effort needed to support persistence. Indeed, a smooth start is considered so critical today that developers have taken note and endeavor to minimize the difficulty of onboarding of new students to their ed tech. (Sharma, Vanek, & Webber, 2019)

Recruitment, screening, and orientation are the subject of the first half of IDEAL’s Distance and Blended Learning Handbook. These early chapters focus on guiding practitioners through a process of determining 1) who to recruit and how to reach them, 2) what skills are needed for successful engagement and how to assess potential learners for them, and 3) what to include in an orientation to learning where the learner gets to know the distance education or blended learning instructor and has time to address a wide range of issues that prepare learners for a successful and positive experience in distance or blended learning. In this post, I’ll briefly introduce key ideas about each of these topics.

Recruitment

Will you deliver strictly distance options? Will you attempt to provide blended learning opportunities? The programming you want to create and the type of learner you suspect will persist determine who you recruit. Your decisions about this will rest on what you determine about your program goals and its capacity.

Take stock of the resources you can make available to learners.

Knowing who to recruit and understanding your means to support them go hand-in-hand. For example, if you know there is no capacity for offering access to computers and internet, do not recruit learners who lack home access unless your chosen curriculum is mobile friendly. If you are able to purchase a license for a core online curriculum, decide whether the product should be tailored to a particular group of students or one that serves a variety of learners with different educational needs. Recruit only those learners who fit the profile of that curriculum.

Identify the characteristics that will improve a learner’s chances of success.

Whether you are teaching in a blended, hybrid, or distance format, successful students are likely to be self-motivated, able to work independently, and possess strong study and organizational skills. Additionally, they have access to the technologies required to participate in learning and sufficient digital literacy to solve problems that arise as they learn.

Decide where to recruit for new students.

Recruiting in classrooms. For blended learning, it is often best to start recruiting with your current students. Because they are known, teachers will have more information about whether they possess the characteristics described above.

Recruiting in the community. In the early days of adult education distance programming, programs conducted recruitment in the broader community using low tech approaches—flyers posted in libraries, community education centers, and restaurants frequented by English language learners. These methods are still useful, as are public service announcements or advertisements in local newspapers, public radio stations, and local cable channels. Also consider posting information about distance education on your website and in social media.

Students who find you through these websites have at least sufficient mastery of the technology needed to find you online. Providing an application form on a website can serve as a way for such a learner to contact your distance education program administrator and also demonstrates adequate digital literacy skills for online learning.

Recruiting within workforce development and other partner organizations.

The Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA) offers motivation for collaboration with workforce development partners, including shared outcomes and a no wrong door approach spelled out in WIOA. Also important is a shared imperative to use technology to help adult learners and job seekers better prepare for careers and further education. Reach out to partners and ask them if they will link to online information about your program on their websites. Make sure job counselors know about your distance options so they can refer learners to you.

Screening

Programs offer distance or blended learning to expand learning for current learners or try to reach new learners.

While these are good reasons to start using distance education, without careful coordination and marshaling of resources, the learners who start in the programs are not likely to have the support they need to persist unless there is careful planning. What sometimes happens is a churn of orientation for new learners, constant follow-up to connect with learners who are not participating, and work to exit learners who have fallen off the map. Past IDEAL member states all seem to have stories about how this scenario played out and sabotaged new distance programming. Because resources in adult education are often in short supply, distance education programs have a finite amount of staff time available to support learners. Ideally this time is used in facilitating students’ learning. To prevent that staff spending a disproportionate amount of time on administration and keeping track of learners, limiting the number of learners in a distance education program might actually strengthen the program. Screening can help you determine who they are.

Alignment of learner knowledge with proposed curriculum

It is important to determine if a potential student has the requisite skills (e.g., reading proficiency and computer competencies) needed to participate in online learning. First, this requires that instructors be familiar with the curriculum and instructional materials available for distance or blended learning. Then, teachers need to examine a student’s academic skills and knowledge, which can be done with a formal assessment tool (e.g., MAPT, TABE, CASAS, or BEST) and/or by informal means (e.g., observing the ease with which they read materials about the program and listening to their oral English skills as they talk to the teacher).

Assessment of non academic competencies

Learner persistence and success in distance education depends on more than students’ academic skills and knowledge. Distance and blended learning require that students be able to organize their time, work independently, have good study skills, and solve problems using technology. Students who lack these skills are apt to flounder in a distance program. Non-cognitive skills become very important in distance education, where students are not enrolled in an onsite classroom-based course and teachers may meet with their students a limited number of times over an entire course, with the remainder of the communication occurring by telephone, email, or through online learning features.

Habits of Mind have been defined as the behaviors required to support learning and successful application of the knowledge that students already possess (Costa and Kallick,2000). Behaviors most relevant for distance learners include:

- Persisting

- Thinking and communicating with clarity and precision

- Thinking flexibly

- Striving for accuracy

- Questioning and posing problems

- Applying past knowledge to new situations

- Remaining open to continuous learning

These habits come into play when one is faced with a challenge or needs to solve a learning problem. Habits of mind assessments can be found on the website of the Habits of Mind Institute.

Problem-solving skills

Development of learner ability to solve problems that require technology (or to solve problems caused by technology!) is a current prioritized initiative in adult education because in today’s world such skills are central to success in online learning. Essentially, problem solving is required when a person is faced with a non-routine task, like they forgot their login information or their wifi access has been interrupted. Getting back to the learning requires sorting out such problems.

Aptitude for online learning

There are several online self-assessments that help students determine whether learning independently online (in either distance or blended models) will work for them.

MNSCU Distance Learning Quiz—The Minnesota State Colleges and Universities system offers an online education readiness quiz covering motivation, learning preferences, time management, commitment, academic readiness, and technology skills/computer access.

Penn State Self-Assessment—This brief quiz provides a feedback related to time management, study skills, personal organization, and technical skills.

I encourage you to explore the recommended resources, consider the requirements of your distance or blended program, and then create your own. Google Forms and Survey Monkey are both useful tools for gathering, organizing, and storing information. If your agency has Adobe Acrobat Pro, you can use that to create forms that automatically transfer gathered information to a response file.

Digital literacy skills

Basic computer, telephone, and tablet skills (e.g., proficiency with common computer applications, Internet browsers, and use of email) are a necessity for students studying online. It is also critical that learners have a basic understanding of how websites and hyperlinking work because conventions for print on the computer differ from conventions for print on the printed page. You might have students take a few of the Northstar Digital Literacy assessment modules to determine where their digital skill gaps lie.

Computer and internet access

In a classroom setting, educational materials and technology are generally made available to the students (e.g., computer labs, tablets, and the Internet). This is especially important for learners who do not have home access. Minimally, if you cannot provide access, make sure learners know about local public access points like a library or a cafe. You might also tell them about www.everyoneon.org/adulted, where they might find access to low-cost home broadband deals.

Skills training

If a student does not have all of the requisite skills, additional training may be required before allowing the student to study at a distance. You may wish to do an analysis of the online materials that are used in your distance and blended learning and then focus training on the skills needed for student success and persistence.

Orientation

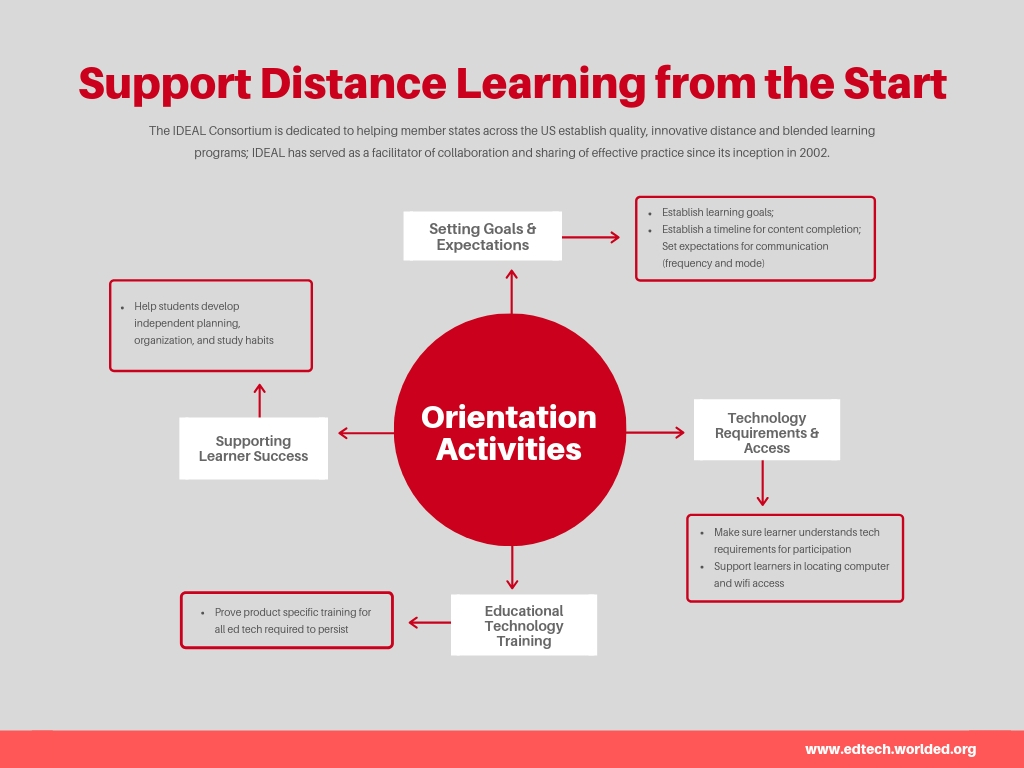

Porter and Sturm (2006) found that learner persistence in distance education programs was connected to the quality of the orientation received prior to instruction. A key attribute of successful orientation programs was the time spent building a relationship with the instructor. A carefully planned orientation can also provide time to address a wide range of issues that prepare learners for a successful and positive experience. During the orientation, students build rapport with the teacher and are introduced to the curriculum materials and to the concept of working, at least in part, independently.

Teachers can use orientation time to help students set goals for participating and clarify expectations for course participants. Study skills, strategies for working independently, and computer skills can also be addressed. Finally, orientation provides a way for teachers to take care of “housekeeping” details, such as collecting contact information (e.g., a telephone number, email address, or Skype name). This orientation is best accomplished face-to-face.

Determine setting and length of the orientation. Most orientation sessions in programs across the US are a few hours long, and can stretch to over a day if TABE testing is part of orientation. The following activities are a must at any orientation.

To what extent does your program employ strategies for recruitment, screening, and orientation? If you are noticing that you’re not doing much of what was presented here and you know you have a persistence issue, consider stepping back and assessing how your current efforts might be adjusted to offer a more solid foundation for the learners who participate. Do explore the Handbook chapter on recruitment, screening, and orientation for more ideas and feel free to post questions below. We look forward to hearing from you!